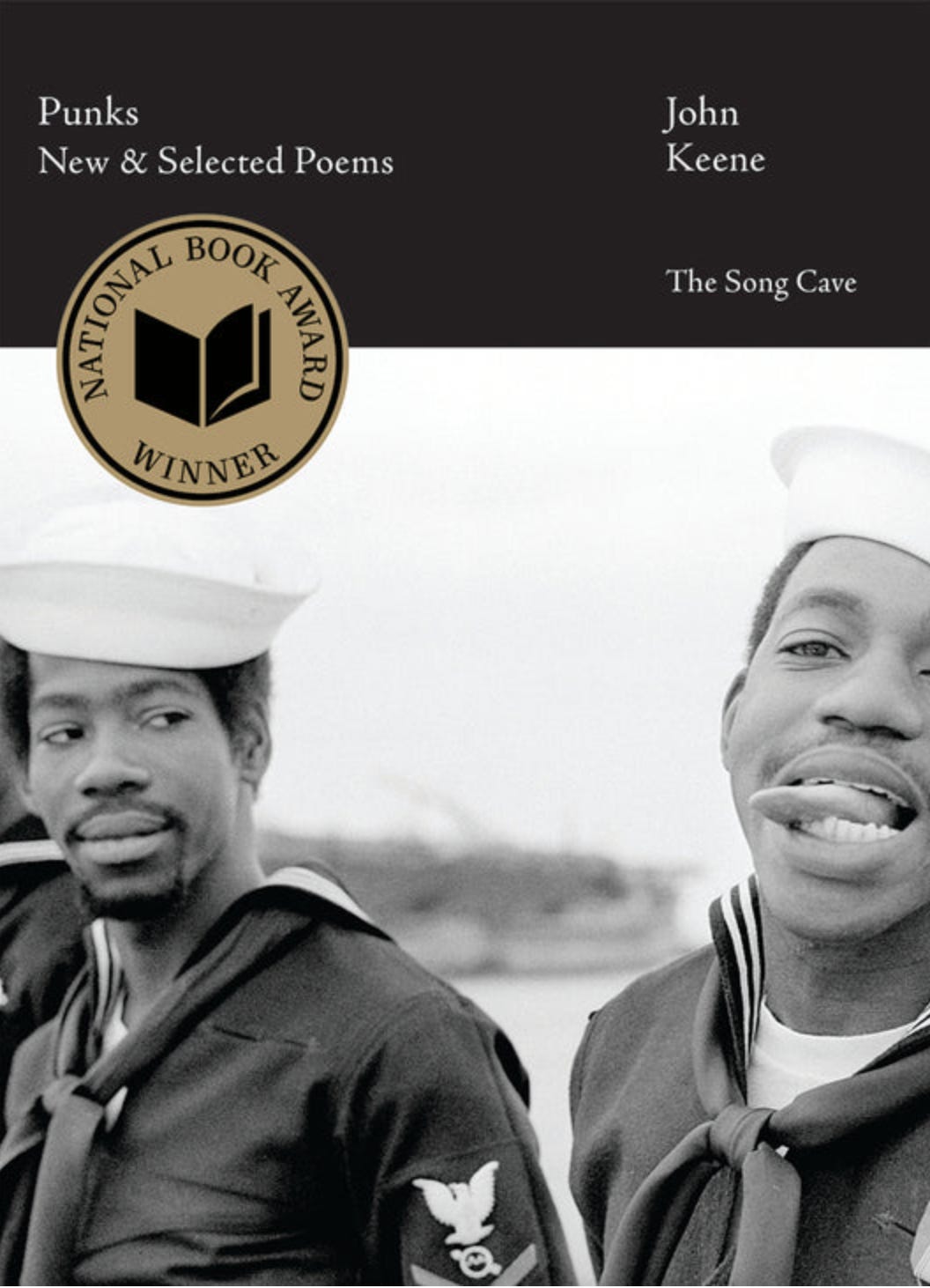

I’m reading John Keene’s Punks: New & Selected Poems. Slowly. A poem a day. Sometimes, a poem every few days. I am still in the first section, Playland, a loving, tender mapping of gay living in an earlier period. Poems are named for bars and cities and streets, spaces of pleasurable tension and sociality. Flirting is social and playful, seduction mutual and consensual. The pace is meditative, rather than frenzied. It has the richness of memory, even of nostalgia. I do not think nostalgia is a bad word.

Perhaps what I mean is this: much of the Black gay work I read from the 80s and 90s—the little I could find, and there wasn’t much—was written from within the deep urgencies and emergencies of the period. It had the fire of the Black Arts movement that preceded and, in some ways, gave rise to it; the political commitment it learned from Black feminism, which gave it space and taught it voice; the rage against antiblack state violence under Reagan; and the fear and urgency of the AIDS pandemic. In all that, it had moments of tenderness—Melvin Dixon and Essex Hemphill wrote some of the most tender poems I know. And there was seduction. But there was also a sense of shortened time. I would find a new poet to read, only to discover that they had died recently. A deep sense of melancholy pervaded the work. So many poems were elegies, even though not named as such. You read Marvin K. White and G. Winston James and weep.

And, perhaps, my own sense of melancholia colors how I read these poets.

I have thought about John Keene’s memory work for a long time. On J’s Theater, his longstanding blog, since 2005, John regularly eulogizes writers and poets and artists and musicians. John describes his blogging as a labor of love. A “(partial) record” of his life. I have long experienced it as a record of how to live with others, how to extend oneself into everyday intimacies, and how to honor our shared living.

I think of it, also, as an ongoing experiment in memory work.

We like to say, “you will never be forgotten.” It is one of my least favorite promises. We forget people. But we can mark that they have been here and have left a mark. A mark can be initials scratched onto a school desk or a heart carved onto a tree or a stubborn grease stain on a couch. It can be a dent in a wall or a scent from a tree planted long ago. We imprint on each other in all kinds of ways. Perhaps what remains is a sense of texture, the flavor of the night, the ghost of long-ago kisses.

And what might we do with those memory-making moments that are fleeting, that are not grand narratives with clear beginnings, middles, and ends, but flutters of joy or irritation. How to write the “Never found again” and the “never heard again,” that is also never “forgotten” (“Nights of 1985”). To recall the pleasures of an older bar where patrons are “gossipping about TV show stars, / garnished paychecks, the Celtics” (“Playland”). Or to recall “the night two tall drag queens / tall as Masai threw down in front of the Dumpsters, / hurling pumps and wigs like gladiators” (“The Haymarket”).

Perhaps what I also mean is that John’s poetry is generous in what it observes and records and remembers. It describes how we make lives with others. The textures and sounds of the spaces we borrow and occupy.

From John, I continue to learn how to linger on the small, the ordinary, the everyday. How to give weight to the moment, and to relish the banality of memory. I am not after the (deceptive) seductions of epiphany or the intensity of ecstasy, even though these are welcome when and if they happen. Nor do I need the poetics of Black gay life to transcend anything. Rather, it is the funk and intricacy of relation that intrigues me.

A song plays. Sweat beads. Glances are exchanged. We move.

beautiful. his work and yours.